Introduction

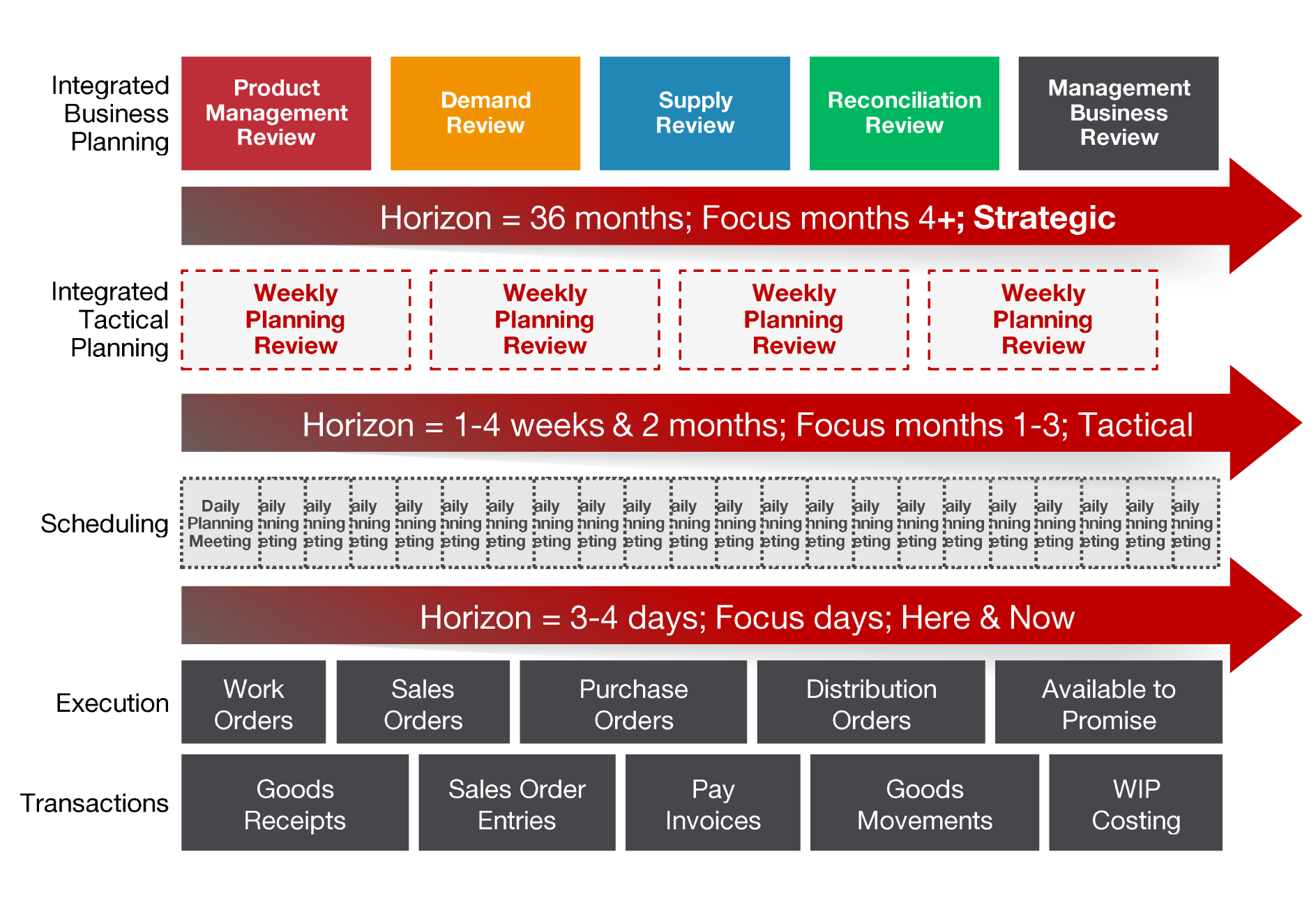

Many companies that have embarked on an Integrated Business Planning implementation still find senior managers being dragged into short-term tactical issues and problem-solving. Despite putting considerable effort and energy into executing their plans, many still struggle with poor customer service, high costs, and high inventories. While Integrated Business Planning is highly effective in aiding planning over a four to 24- or 36-month horizon right down to EBIT projections, it was never designed to control the execution of those plans within the one-to-three-month tactical horizon. This is the role of Integrated Tactical Planning. Unless plans are properly managed and coordinated during this time period, execution is problematic. The constant last-minute changes and “firefighting” that plague the business also lead to high levels of frustration.

The importance of ensuring a process such as Integrated Tactical Planning exists is particularly topical given the unnerving climate of uncertainty and the challenges facing many organizations right now. The time frame in which decisions must be made has shifted from years and months to weeks and days. This is where Integrated Tactical Planning – synchronized processes with clear responsibilities and expected outcomes – can help.

The successful deployment of Integrated Tactical Planning will define and calm the process of management and communication in the execution window, creating the integration between the various functions within the organization, and ultimately leading to improvements in customer service, inventory levels, and other key metrics.

When Should You Think About Integrated Tactical Planning?

Table 1: Symptoms of Non-Integrated Processes

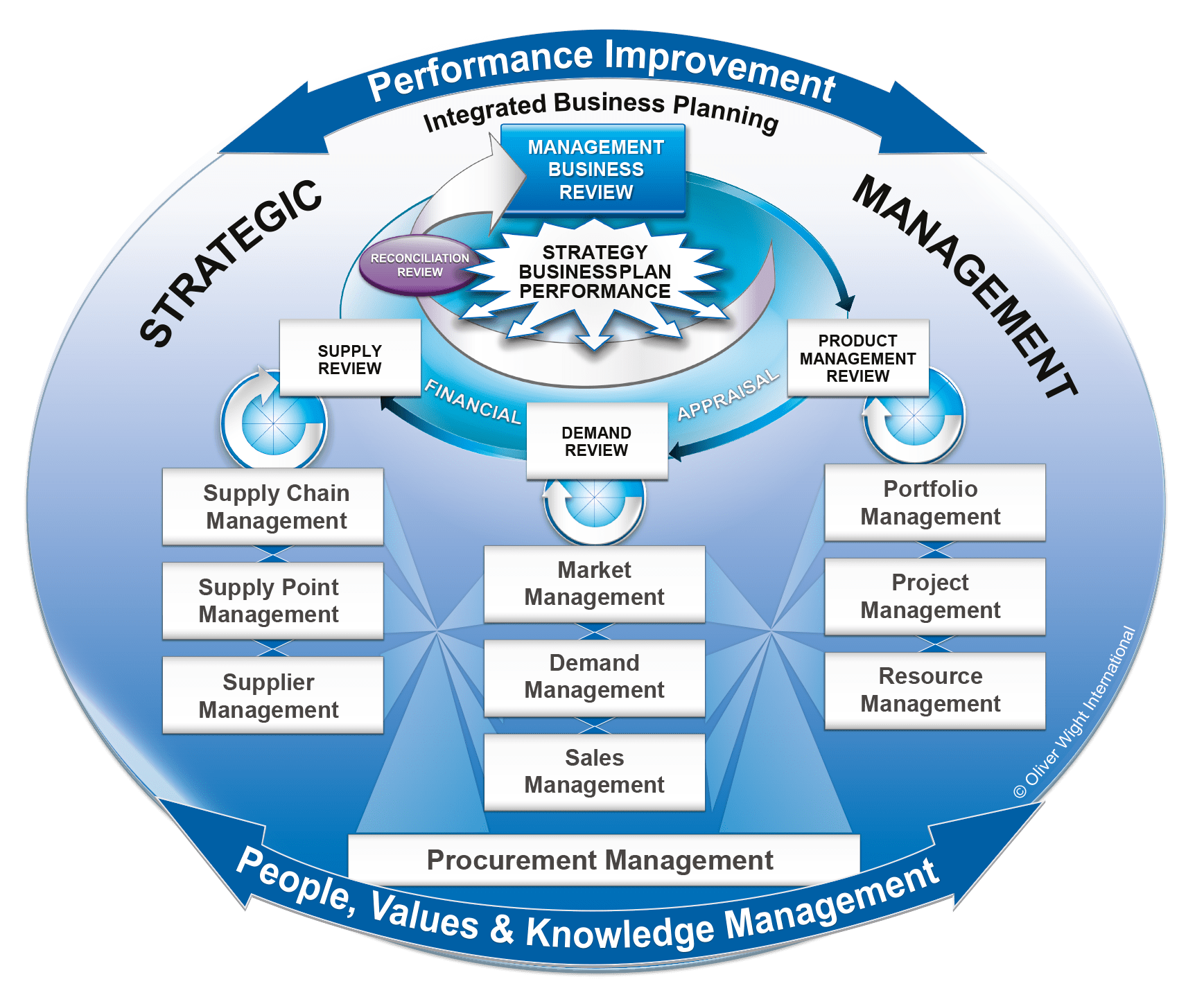

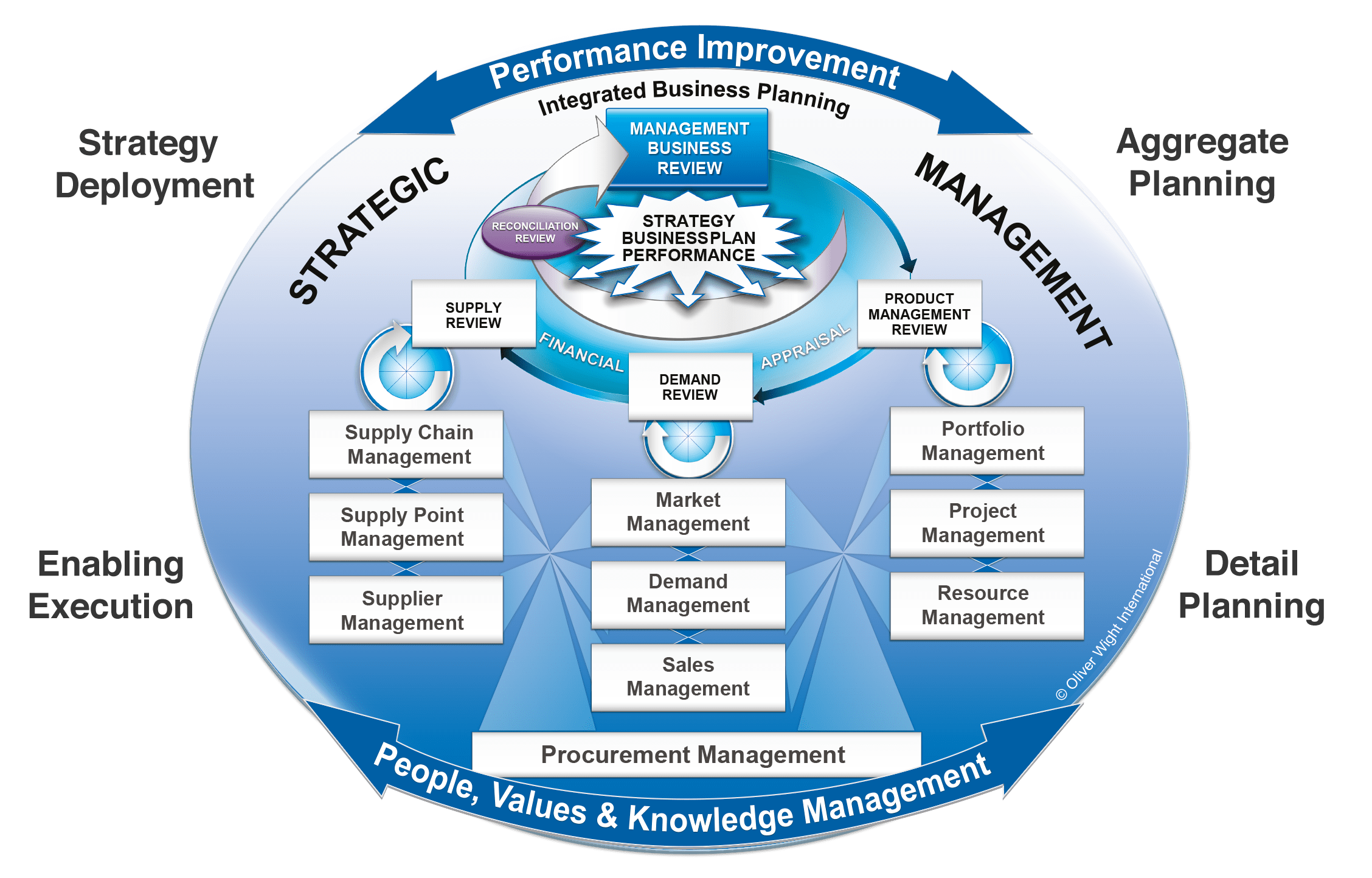

As the table above illustrates, there are many symptoms of a failing planning process and it is a common misconception that deploying S&OP (or more likely, its latter-day incarnation, Integrated Business Planning), will fix these issues. Integrated Business Planning is a powerful decision-making process that sits at the heart of the Oliver Wight Integrated Business Model (Figure 1) and is the means many organizations now choose to run their entire business. However, as the Model shows, Integrated Business Planning cannot work in isolation; it needs to be supported by equally effective monthly (re-) planning, and weekly and daily execution processes. Thus, the Integrated Business Model is a deliberately designed, and all-encompassing set of processes, which integrates the annual business planning cycle with the daily execution of plans, ensuring everybody within the organization is aligned with a single game plan in support of the overall business strategy.

Many organizations mistakenly find themselves deploying a monthly Integrated Business Planning process, which is meant to create plans and give the Executive visibility over 24 to 36 months, but without paying attention to how those plans are to be executed, compromising the intent of Integrated Business Planning. Typically, they try to use the Integrated Business Planning process to manage both the longer-term planning horizon and shorter-term execution horizon. Another common error is setting up a weekly Integrated Business Planning process, which by definition is not Integrated Business Planning at all.

Without Integrated Tactical Planning within the short-term planning and execution window, it is inevitable senior managers will be drawn into spending their time on day-to-day problem-solving, rather than longer-term decision-making.

Integrated Tactical Planning is part of the “below-the-line” processes within the Integrated Business Model (Figure 1). The objective of an Integrated Tactical Planning process is to take control of the signed-off Integrated Business Planning plans and ensure they are being deployed at a weekly and daily level. Any significant changes are then formally managed to continually re-optimize plans in the short term or communicate otherwise. Most companies do some of this but tend to overly rely on good people, rather than well-designed processes and formally defined ways of working. The intent of Integrated Tactical Planning is to focus on cost-effective management of change and deploying the Integrated Business Planning plans.

Figure 1: Integrated Business Model

“It is useful to think of Integrated Tactical Planning as the cogs in a gearbox - it doesn’t matter how big or small those cogs are if one is broken, the car stops. Each cog relies on the next, but a clutch is required to separate them and change gear to speed up, climb hills, slow down, or prepare for tight cornering. To do this requires mechanisms to be designed into the gearbox in the first place, and not force-fitted afterward.”

Many companies are usually doing some of this, but usually not bringing it all together. The intent is to align, the more-detailed, below-the-line processes, back up to the aggregate monthly re-planning Integrated Business Planning process, every week. It is specifically designed to keep senior managers “out of the weeds”, but, the temptation can be too great. Because all senior executives have come up through the ranks in at least one discipline, they can be very comfortable at that level of detail.

ITP Definition

Integrated Tactical Planning is a crossfunctional, middle management process that routinely re-aligns and re-optimizes core process plans (product, demand, and supply), and facilitates effective communication, should re-alignment not be possible. This is done weekly, typically over a 13-week horizon.

It considers changes to the plans and, as required, escalates decisions to senior levels.

A primary objective of the process is to ensure execution of previously agreed Integrated Business Planning process plans. ITP helps senior management to focus on the four-to-24-month horizon and in the process helps liberate the organization.

Figure 2: Definition of Integrated Tactical Planning

"Integrated Tactical Panning (ITP) ensures alignment between the monthly plan, and what is done day-to-day"

The Integrated Tactical Planning Time Frame

The time frame for Integrated Tactical Planning is usually referred to as the time fence or the planning time fence. The most precise way of defining this planning time fence is when expenditure on variable and semi-variable expenses begins. For example, in a manufacturing or physical goods environment, the lead time for purchasing materials and products could be several months for items sourced overseas, or weeks, if they are sourced locally. But this is only one time fence the business might be committed to. As shown in Figure 3, other time fences should also be considered: managing customer order expectations, contractual obligations, trade spend and promotional planning and new product introduction.

All these are commitments to spend money on resources to deliver future demand requirements competitively and cost-effectively. Whereas the monthly Integrated Business Planning process manages resources and supply to meet the demand plan, the key concept of the Integrated Tactical Planning process does the opposite and manages demand to meet the available resource and supply plans inside the planning time fence. This is because the closer you are to executing the plans the less ability you have to make changes, and the greater the cost of those changes and the chaos created by change. Stability is critical.

Figure 3: Managing Time Fences

Managing Business Plans

The core plans for Integrated Tactical Planning are the same core plans used in the Integrated Business Planning process just at a lower level of detail such as by SKU and by hour/day/week compared to family/month. There are also "resultant plans", which are not discrete plans, but plans derived from and dependent on, the core plans e.g. financial outcomes and projections, and inventory projections.

Product Portfolio Plan

A key assumption is that before projects reach the Planning Time Fence, the entire portfolio is considered and there have been effectively managed project plans for each project, including appropriate resources allocated. In so doing, the following factors are considered:

- Readiness for launch – products are in the final stage before launch and it is critical to ensure everything is ready to go, from product availability and distribution, to sales team preparation, advertising, and public relations;

- Product Portfolio changes which are in the final stages of execution and will include executing the phase-in and phase-out plans to minimize potential obsolescence and write-offs;

- Trials and product testing.

Demand Plan

The demand plan is the anticipated product sales plan, out to the planning time fence. While it is often said the demand plan, resulting from the Integrated Business Planning Demand Review, is an unconstrained statement of demand, once inside the planning time fence this is not the case as it is balanced against available resources. As with the product plan, the demand plan is also pro-rated into weekly buckets and phased according to the weekly off-take pattern (see Figure 4 overleaf). This agreed demand plan then serves as a key input into resulting manufacturing and supplier schedules. Financial outcomes are derived from it, and it is one of the inputs in calculating inventory projections. Very few businesses have a perfect demand plan, so it is important that they can recognize changes and deviations from this plan to assess them for feasibility to avoid over-commitment of the available resources.

Supply Plan

The supply plan is the cost-effective response to what has been planned to be sold. These plans are synchronized with the pro-rated weekly demand plan, out to the planning time fence, and in the near term, are likely to be reflected in daily or even hourly phasing. Once inside the planning time fence, flexibility with the supply plan is reduced because materials and goods have been ordered, shifts and labor have been organized, and capacities and storage locations optimized. So, any changes to the plans at this stage will cost money, e.g. items airfreighted at short notice, cut pallets distributed, or part loads transported.

Financial and Inventory Plans

Outcomes of product, demand and supply plans, are the financial and inventory plans. The crucial thing to note here is that these plans cannot be managed directly or discretely. They have a cause-and-effect relationship with the preceding plans. While it is important to test changes against financial and inventory outcomes, the levers remain primarily in the product, demand and supply plans.

Figure 4 shows an example of how plans are pro-rated and aligned with any recurring or identifiable phasing. The demand planning part of the Integrated Business Planning process identifies seasonality or known one-off events, and the plans and numbers communicated that month, phased accordingly. Since these are in monthly buckets, they need to be pro-rated into weekly buckets reflecting the normal off-take pattern. Often companies have really big first weeks of the month, or last weeks of the month, because of terms of trade or promotional activity. Whatever the reason, requirements need to be set up to match this pattern. In some industries, such as fresh milk, for example, a daily pattern also needs to be considered.

The seasonality and weekly phasing assist with managing the "lumpiness", but as with managing lead-times it is important to plan for what is known in the first instance, and then work to remove the causes of the lumpiness over time.

Figure 4: Monthly, Weekly, Daily Phasing

Managing the Integrated Tactical Planning Process

The quorum managing Integrated Tactical Planning will vary from company to company, and by size and industry type, so this section uses generic roles. Each of the four major elements of planning execution requires at least one formally defined role to identify and manage changes to plans inside the planning time fence as follows:

- Managing changes to the Product Portfolio and supporting plans - Product Planning Manager

- Understanding demand and controlling demand-generation levers - Demand Execution Manager

- Understanding supply, and controlling supply and supplier capabilities and costs - Supply Planner/Scheduler

- Managing incoming orders and managing customer expectations - Customer Service/Order Entry

Figure 5 shows how each of the roles and responsibilities interact. The objective is to ensure the many potential influencers for each element are channeled through a small number of key roles and thereby managed effectively.

Figure 5: The Quorum of Roles

Product

This role is more straightforward in most organizations and is typically at the heart of the product development/project management function. It involves coordinating changes to the plan, especially where it intersects with demand and supply requirements and capabilities. Examples include the inclusion of new information related to the timing of new product launches, but also the phasing out of products as part of active lifecycle management. The Product Planning Manager is, therefore, the champion of identifying and managing any changes to the product portfolio plans.

Demand

In smaller companies, the Demand Manager may be responsible for demand planning and control. In larger companies, responsibilities might be split into Demand Manager, Demand Planner, and Demand Execution Manager. However, the demand execution aspect of the role is most important here. It is the responsibility of the Demand Execution Manager to be all over the difference between incoming sales orders and the progression to meet the monthly demand plan. They play a pivotal role in identifying and managing potential abnormal demand and liaising with Customer Service, Supply Chain, Production, Distribution and so on, to fully understand the impact of what can be done about getting back on track.

Successfully executing the above-defined role requires a person who communicates well cross-functionally with Sales, Marketing, Demand Planning, and Supply Planning. The Demand Execution Manager must be comfortable working in the details but also must keep the customer’s perspective and the company’s well-being in mind.

Supply

As with the Demand Manager, the supply planning role may also be performed by one person or several people, depending on the size of the company. Unlike the demand manager role, however, there is a plethora of different job titles and descriptions, so for this document, we will use the title "Supply Chain Planning Manager" to describe the most senior role. The Supply Chain Planning Manager is considered to be the person who is managing the supply plan within the planning time fence process. Their primary responsibility is to cost-effectively meet the changes in demand and to zealously guard the stability of the plan – unless the benefit of the change can be demonstrated to outweigh the cost.

Customer Service/Order Entry

Often overlooked for its insight into customer buying habits and demand levers, Customer Service can play an extraordinary role in maintaining stability of supply plans inside the planning time fence. Again, in smaller organizations, Customer Service/Order Entry, order promising are likely to be a single role; in larger organizations, it could be several individuals with specialist category or channel responsibility. It is, however, the order entry and promising role that is most relevant to Integrated Tactical Planning - promising to the forecast and communicating wherever this is not the case.

Financial Integration

What about the Finance Team?

Although not explicitly called out, the Finance community is also a key player in all these discussions, both to ensure that a financial view of the decisions is understood but also to avoid surprises for the IBP process at the end of the month.

Oliver Wight colleagues can offer the following insights into the role finance plays in ITP:

Finance plays a supporting role in ITP.

The primary players in ITP are those that execute the operations plans for product portfolio, demand, and supply. The short-term tactical objectives are to maintain the integrity of these plans and to maintain customer service and other trading partner commitments in the face of short-term changes due to unforeseen events. As such, while financial impacts are a consideration, they aren’t typically the driver of such short-term decisions (this week, this month).

Finance supports scenario-based decision making.

While financial implications of weekly execution changes can be “intuited” by those executing the operational plan (e.g. based on roughly right rules of thumb), finance can be called upon as an “analytical partner” to provide financial analysis for different decision scenarios. It is not the intent that Finance gets involved in every decision but that the organization defines when to bring the analytical “muscle” that the Finance team can provide in to play. Establishing the criteria, defining the circumstances and level of materiality when Finance should provide analysis is key to maintaining an agile environment. Especially in an integrated system enabled by IBP, Finance often has planning templates that can be used to quickly turn around a roughly right financial-based analysis.

Finance should provide a bridge between the decisions made in ITP and the forward implications for the longer IBP planning horizon.

Finance assures integrity of the IBP Financial Appraisal process by “picking up” the material ITP changes throughout the monthly IBP cycle. These changes might impact revenues, costs and/or assets, especially inventory and other components of working capital. Finance also reflects changes in the updated IBP forward financial view by incorporating the impact of ITP decisions, as appropriate, in the IBP plan in line with defined escalation criteria. As part of the Financial Appraisal/Financial Review process, it can advise whether the cumulative ITP decisions are driving a larger or smaller gap to the annual plan goals and targets. This might cause future ITP decisions to reconsider the basis of the “rules of thumb” approximations.

In summary, Finance should help with ensuring that the ITP team have up to date cost information in order to make decisions. Finance also has a key role in identifying the key drivers of financial outcomes through the IBP process, communicating that to the ITP team as focus areas, and establishing escalations when these key focus areas deviate from the plan to enable the entire organization to detect issues, escalate and take corrective action sooner versus later.

Figure 6: Finance – ITP Key Responsibilities In Robust Process

Integrated Tactical Planning Leadership

This is dependent on the size and complexity of an organization and the level of change that is routinely experienced in the execution phase. In a smaller organization one of the quorum, mentioned above, operate as the leader in an extension to their normal role. In other organizations the range of leaders noted with clients includes the following:

- The Integrated Business Planning Manager;

- A full-time Integrated Tactical Planning Manager;

- The Supply Chain leader with responsibility across multiple nodes of the supply chain;

- Regional Distribution Manager, in a predominantly distribution business;

- The Site Manager in a discrete manufacturing environment.

As will be discussed below, the structure is an important guiding factor, but many organizations are realizing the importance of the process and moving more to dedicated roles.

Decision Making

The working hypothesis is "silence is approval". This means that as plans are signed off, through the monthly Integrated Business Planning cycle, the executive and other senior managers can safely assume that plans are on track unless they hear to the contrary. This includes assuming that the weekly plans out to the planning time fence are also on track or being appropriately managed.

The cascade of plans is depicted in Figure 7. The important characteristic of this hierarchy is that it relies on key roles at each level, understanding both their responsibility and authority, to know when an issue should be escalated. This saves many people-hours and truly empowers individuals to make the right decisions, at the right time, throughout the organization.

So, as each day, week, and month passes, the model allows for proactive gear changes to shifting circumstances, rather than costly uncontrolled reactivity or firefighting.

Often during Oliver Wight coaching and change management programs, it becomes apparent that the organization is erroneously treating all its customers, and SKUs the same.

Figure 7: Monthly, Weekly, Daily Plan Alignment

It is vital that once the value proposition or unique selling benefit has been agreed, the decision-making and escalation criteria are defined based on a customer versus SKU Pareto. While this forces people to think hard about the trade-offs, once done, it also gives them direction on how to make decisions as plans change, which all functions in the business have agreed with in advance. It is often the case that organizations leave very important decisions such as which customers will receive stock in times of short supply to someone at a relatively low level in the organization, while the same individual isn’t permitted to buy stationary without obtaining multiple signatures of approval.

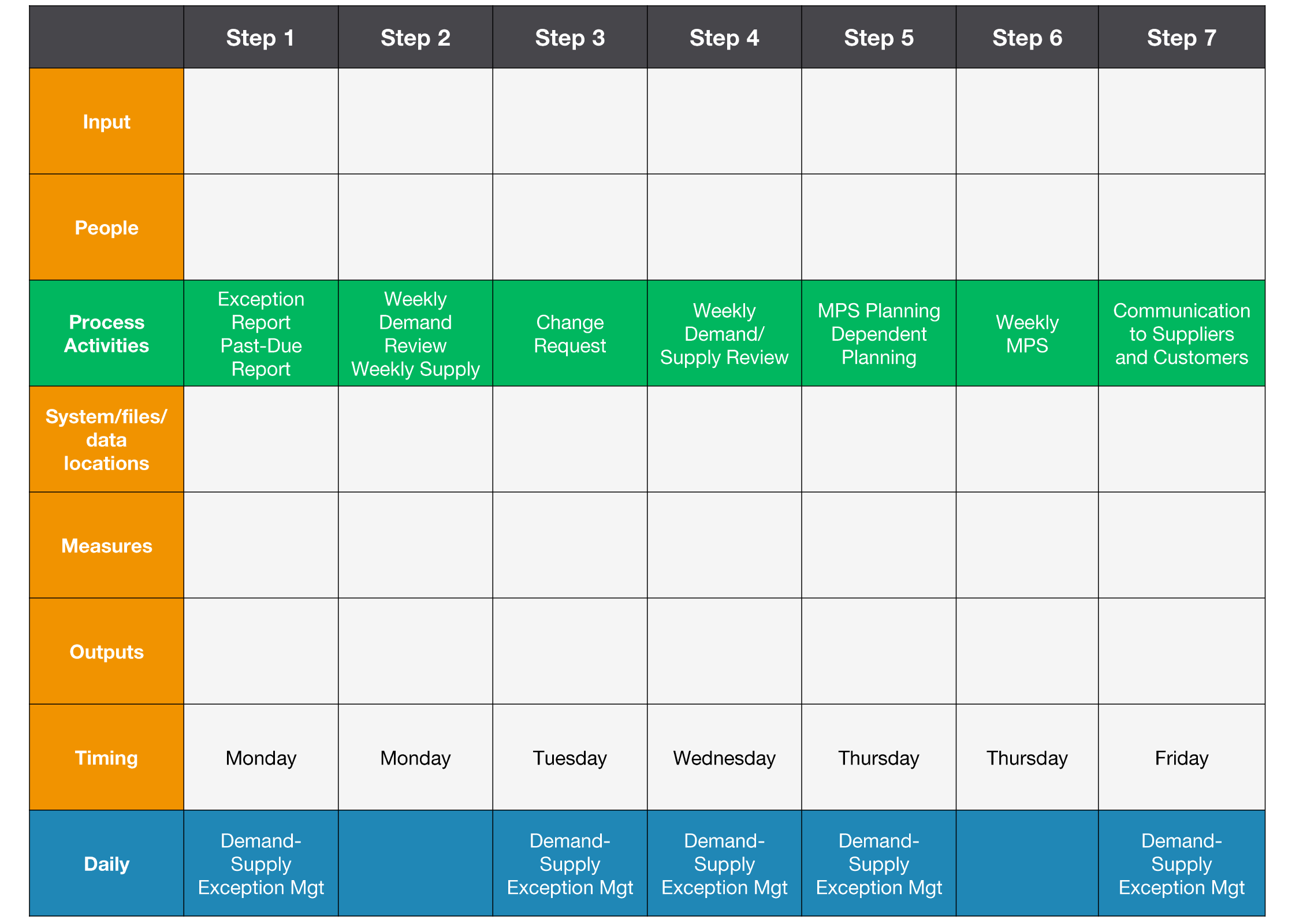

The Integrated Tactical Planning Sequence

Weekly Review Meeting

Integrated Tactical Planning is a continuously operating process, managed through the key roles identified earlier - every hour, every day. It is important, however, to conduct a weekly review of the regenerated plans, to formally agree that the re-cast plans resulting from changes, which have occurred during the week, are valid and doable. While all business environments are different, the generic flow for this weekly meeting might look like this:

- Key issues to be resolved at this week’s meeting;

- How did we do last week? Having the right level of performance and process metrics to inform us that we did what we said we were going to do, such as on-time/in-full measures, demand variance, data accuracy and demonstrated capability.

- How are plans to go this week;

- Significant demand variance implications on next week and out to the planning time fence;

- Significant impacts on the supply plan next week and out to the planning time fence;

- Agreement on the daily supply schedule for the next two weeks;

- Agreement on the rough-cut capacity plans out to the planning time fence;

- Progress with significant initiatives – value engineering, new product launches, etc.;

- Agree that core plans are doable based on the knowledge we have to date;

- Reconcile latest plans to original IBP plan, including Financials;

- Hedging and flexibility plans;

- Minutes;

- Critique.

To facilitate the review meeting, it is important to formally map each step and activity in the preparation cycle, as shown in Figure 8.

The next step is to define the SIPOC (Supplier of Input to a Process with Outputs going to a Customer) for what happens every day to run the weekly cycle, and whose responsibility it is.

Figure 8: Weekly Planning Process and Meeting

Daily Review Meeting

The final step is to define the daily meetings, which are usually site or facility based. Their purpose is to maintain the ability to supply to the agreed weekly supply plan. A daily meeting closes the loop and ensures that all levels of the process are continually synchronized. An example of a daily meeting agenda is:

- How did we do yesterday?

- What is on for today?

- Any issues with doing the plan for tomorrow?

- Will we meet the weekly plan as agreed at last week’s Integrated Tactical Planning meeting?

- What is to be escalated, and to whom?

This meeting should be no more than 15 minutes and may contain other items, such as safety performance. The important part is that it is about plans and performance, not just performance, as occurs in most organizations.

Figure 9: Weekly Planning Process Steps

Structure

Integrated Business Planning is an aggregate business planning and management framework, which means it is deliberately designed not to operate at a detailed level. Integrated Tactical Planning, however, is meant to operate at a more detailed level and therefore requires a different structure to the Integrated Business Planning process.

In the interest of keeping it simple, the default position is to run only one Integrated Tactical Planning meeting and process, and in most small organizations this is possible for the weekly review. In larger organizations, however, the level of detail required to make good decisions becomes so great that just one meeting and process is not possible. In most organizations, the daily review meeting is often multi-stepped as it can start life as part of a shop-floor shift handover process and escalate up to give middle or senior leadership a view of the current status.

Guidelines for making decisions on how to structure the process:

- Number of SKUs, sales channels, and go-to-market strategy/level of supply chain segmentation;

- Number of manufacturing sites, distribution centers, and geographic locations;

- The level of common or discrete resources to support demand, supply, and inventory plans.

If more than one process is required, this is often referred to as a matrix, because each process needs to be defined, not only in terms of what that process is covering but how it then relates to other Integrated Tactical Planning processes and Integrated Business Planning processes.

In most cases, the structural question can be addressed at the design and deployment stage. It is highly recommended that deployment follow Oliver Wight’s Proven Path, (this has been dealt with in many previous publications, so we won’t go further into detail here), which recommends a pilot, bullet-proofing and roll-out approach. This means that a narrow strip of the business is chosen to pilot the design. In most cases, this pilot will, in its early phases of design and testing, shed more light on refining the initial recommendations based on the guidelines mentioned above.

The typical deployment approach is four weeks piloting, four weeks rolling out to all other areas, and four weeks refining. The weekly cadence creates a wave of energy, resulting in a fast realization of benefits. It is important to recognize, however, that there needs to be a sustainability plan, and a solid overarching Integrated Business Planning process in place, to continue the flow of benefits for the longer term.

Figure 10: 10 Key Components of ITP

Conclusion

If your Integrated Business Planning process is not delivering all you think it should, then it may be lacking integrity in terms of what is being done week-to-week, day-to-day. Integrated Tactical Planning formalizes the weekly and daily execution processes and aligns them with plans signed off in the monthly Integrated Business Planning cycle. Thus, key operational metrics see a step-change in improvement, and time is released for people to spend on longer-term activities. As a result, both long-term and short-term business goals can more easily be achieved. In a world where the one constant is change, Integrated Tactical Planning helps organizations assess both the impact of changes in the near term as well as a framework for effective decision making required to maximize performance.