Introduction

Managing the eternal struggle between too much inventory and not enough lies at the heart of effective supply chain management, but it’s an equation organisations continually fail to get right.

It’s a typical situation; the business doesn’t like the amount of inventory it holds, so an edict is issued to reduce it. Production stops until inventory is cut to an acceptable level, only to find, a few weeks later, customers are unhappy they can’t get hold of the products they want. So production restarts and runs flat out for the next few months to try and recover the supply position. The result? The organisation ends up with more inventory than it started with.

However, when it comes to optimising inventory, the choices go far beyond simply stopping production. Effective supply planning is the answer. By properly analysing the decisions it makes regarding service levels, cycle times, the utilisation of production capacity and safety stock, an organisation can create a list of options to ensure it is always carrying the right amount.

Rather than wait for the next brave soul to just stop production until inventory runs dry and let history repeat itself, a paradigm shift is required.

Optimum inventory level

It’s only when an organisation can define what inventory it needs to effectively run its business and deliver its objectives, that it can take hold of the ‘inventory monster’ and make lasting improvements. But how does an organisation decide what the ‘right’ level is?

There are many formulas available to calculate what a business’ safety stock should be based on: variation of demand and supply, lead times, and the service level a business sets out to obtain. But that’s the easy bit and before starting down this route the business needs to step back and review the reasons it holds inventory in the first place.

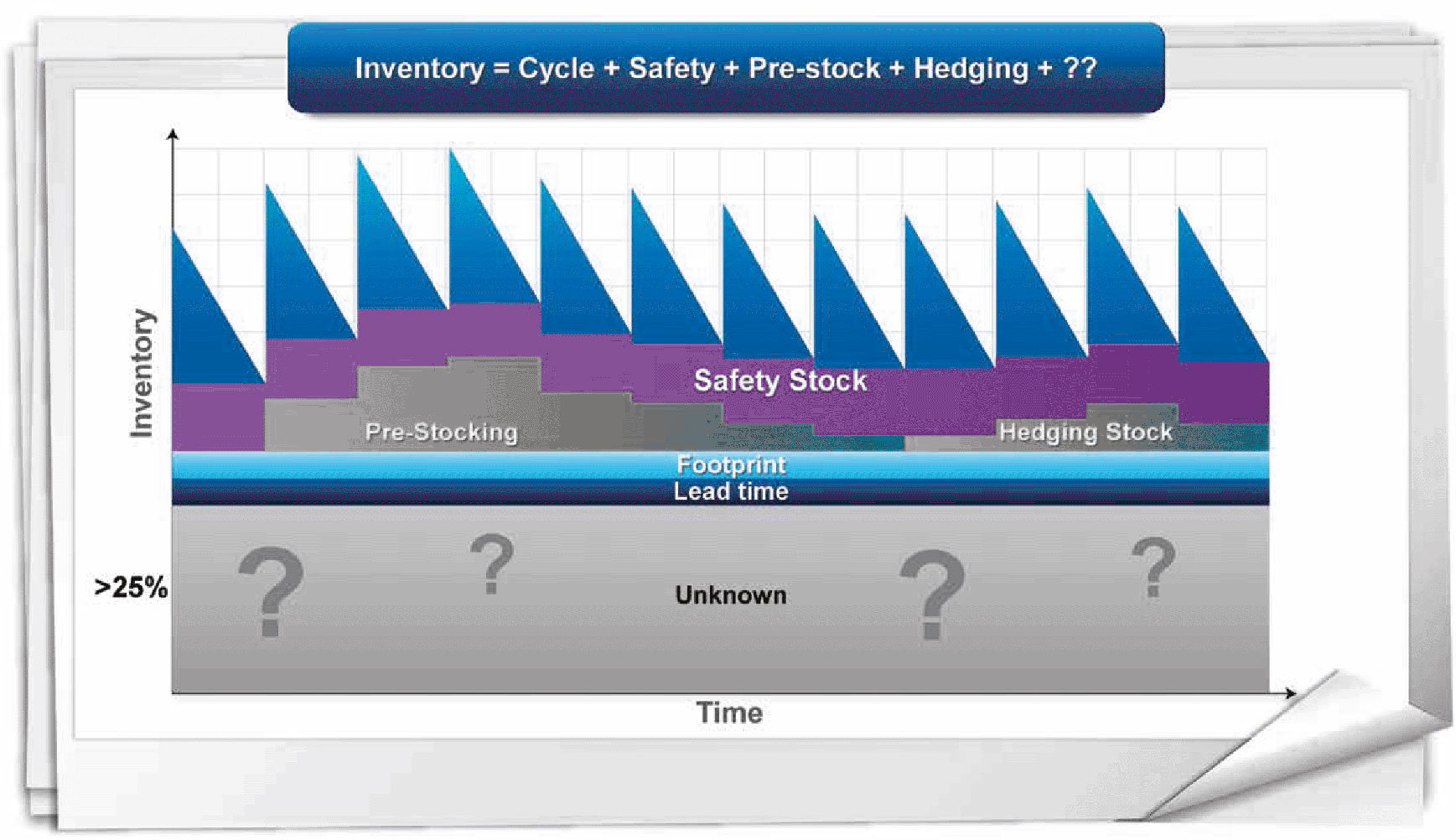

Figure 1: Inventory management

All too often an organisation will rush straight into removing visible inventory (cycle stock, safety stock, pre-stocking and hedging stock). However, as figure 1 shows, it’s the rest – the great unwatched – which can be as much as 25 per cent of an organisation’s inventory, where efforts need to be concentrated.

It’s not enough, however, to simply remove the unknown inventory at a stroke. Trying to remove inventory without tackling the root cause is like tackling the symptoms of an illness before the diagnosis. It is critical to first truly understand why it is there and then to put a well-considered action plan in place to remove it.

Inventory as a consequence

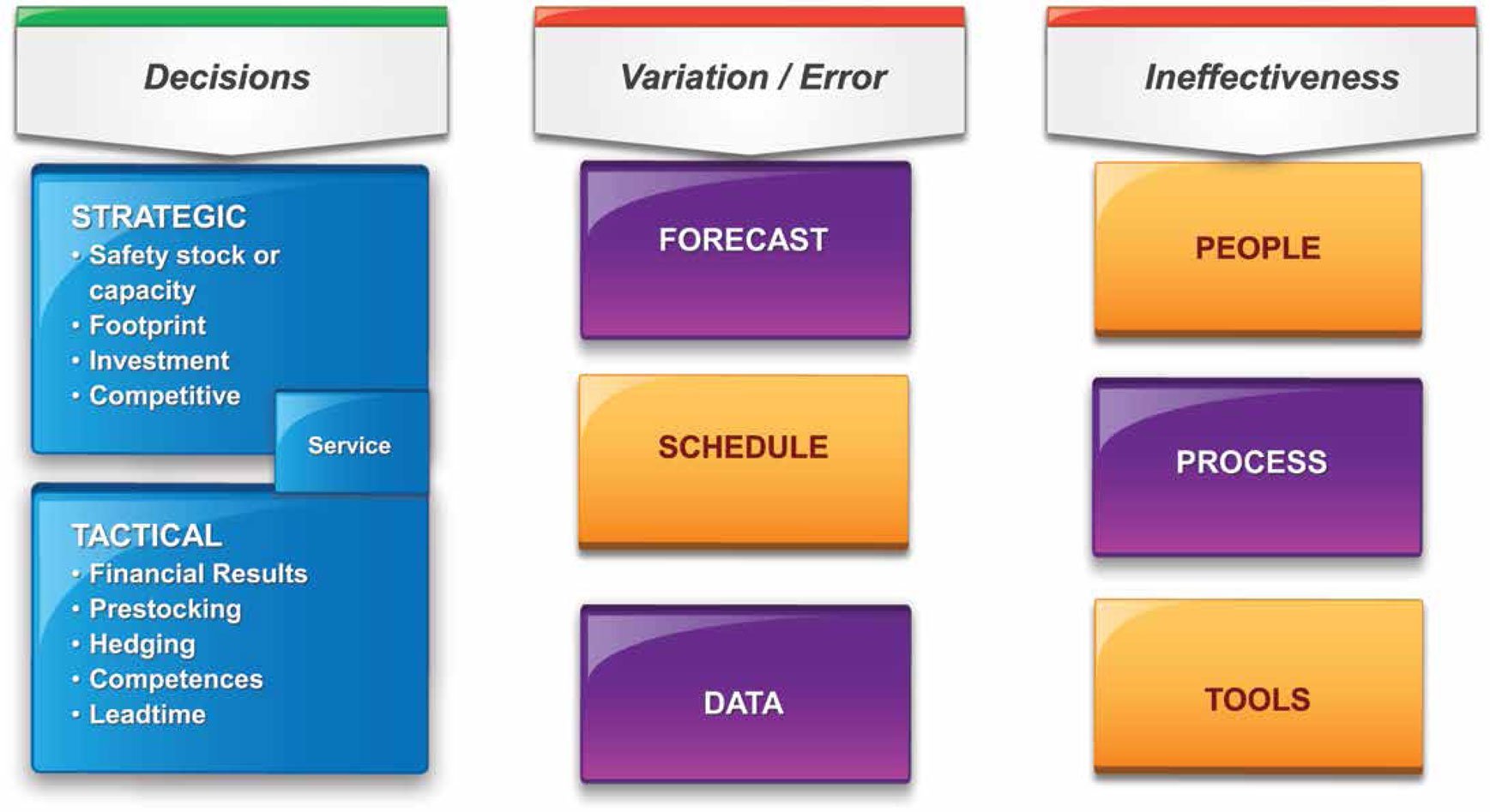

So how is inventory created in the first place? It comes as a result of the many things a business subconsciously does, or allows to happen, which can be classified under one of three headings (as shown in figure 2): variation and error; ineffectiveness; strategic and tactical decision-making. An organisation has to get each of these under control before it can manage its inventory effectively and in turn, become both lean and agile.

An obvious cause of inventory is the variation that occurs between supply and demand; in a hypothetical world where organisations have 100 per cent forecast accuracy there is no need for safety stock. In reality, of course, organisations are often plagued by inaccurate, over-zealous demand forecasts and as a consequence end up with too much stock. Errors too - whether buying the wrong materials, producing off-spec or poor quality products, or using the wrong data in forecasting and planning - result in unnecessary stock.

Figure 2: Inventory as a consequence of...

Less obvious is inventory created as a consequence of the inefficiency of people, process and tools. A common example; companies which do not have an ERP system (yes; there are still plenty of them) and run MRP-type calculations on a spreadsheet will often only do so on a weekly or monthly basis because of the time it takes. Those companies, as a result, will frequently keep a higher safety stock ‘just in case’.

Most fundamentally though, inventory is a consequence of the strategic and tactical decisions a company makes; decisions around the number of supply points in the supply chain, the service levels required, or the level of manufacturing efficiency needed, all have a huge impact on inventory. Strikingly, the inventory an organisation holds today is typically a consequence of the decisions it made months, years, even decades ago. When it makes these decisions, companies fail to recognise the long-term impact they have on inventory, and instead arbitrarily set targets on the basis of a certain number of weeks’ coverage. This leaves those involved in day-to- day inventory decisions with no understanding of, or control over, the levers affecting inventory targets and the poor soul given the title of ‘Inventory Manager’ is often no more than an inventory babysitter, with no real power to influence its existence.

Don’t take inventory down; change the way it’s managed

Once the cause of inventory is understood, it is time to tackle how to manage it. Integrated Business Planning (advanced S&OP) can provide the control over processes, visibility to plan, and effective decision-making, which are critical to getting inventory right.

Integrated Business Planning (IBP) sits at the heart of many organisations as the management process that runs the business, aligning strategic and tactical plans each month, and allocating critical resource - people, equipment, inventory, materials, time and money - to satisfy customers in the most profitable way.

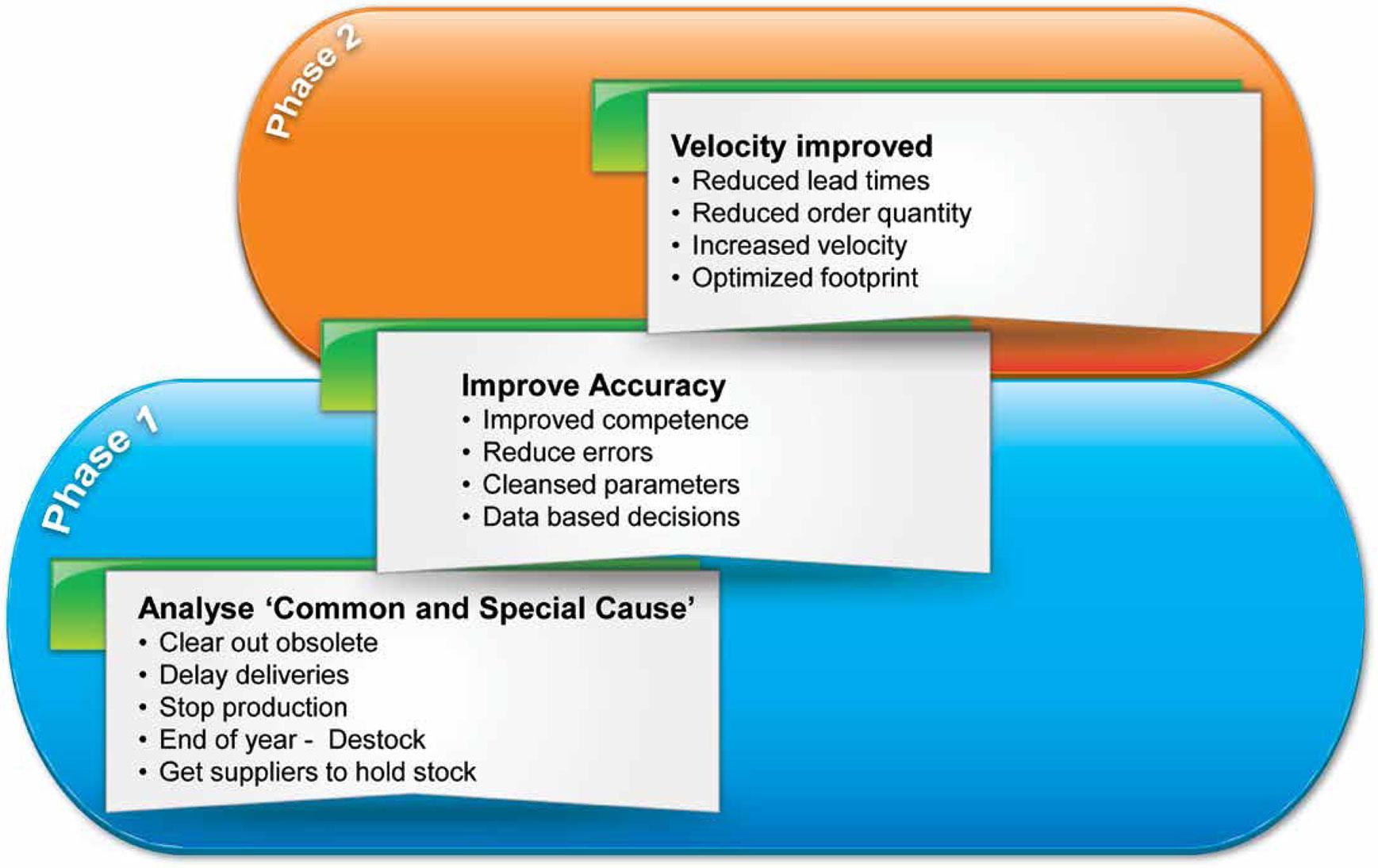

As a business develops its IBP process, it will reach difference phases of maturity, moving from the fire fighting, disconnected management processes of phase 1, to the business process control of phase 2. Figure 3 shows the improvements a business needs to make to tackle the root cause of inventory through this maturity journey.

Reduced inventory as a consequence of...

Figure 3: The Oliver Wight maturity map

In phase 1, ineffectiveness and inaccuracy must be tackled. Here, organisations need to eliminate variation as a priority – removing the big process errors. They must have a good understanding of their business processes and ensure they are executed consistently. For a business to reach the top of phase 1 it must be ‘in control’ and do everything it plans to do, as planned, at least 95 per cent of the time. With the improved understanding and planning an organisation gains in phase 1, it is possible to remove a large amount of the unknown inventory it holds.

At the top of phase 1 into phase 2, organisations will begin to understand the impact of decisions and take account of inventory in the decisions they make. IBP provides the leadership team a clear view of any issues and gaps between planned performances, as set out in the top-down strategic/business plans, versus the bottom- up projection of where the business is actually heading. IBP puts great emphasis on assumptions management and scenario planning, to ensure decision-makers consider all the various alternatives, so they can then choose what they believe to be the best alternative, with confidence.

Inventory Management

As discussed earlier, when it comes to decisions regarding inventory, stopping production is rarely the answer and organisations must consider all the supply variables to manage its inventory effectively, looking beyond the immediate execution window before making critical decisions.

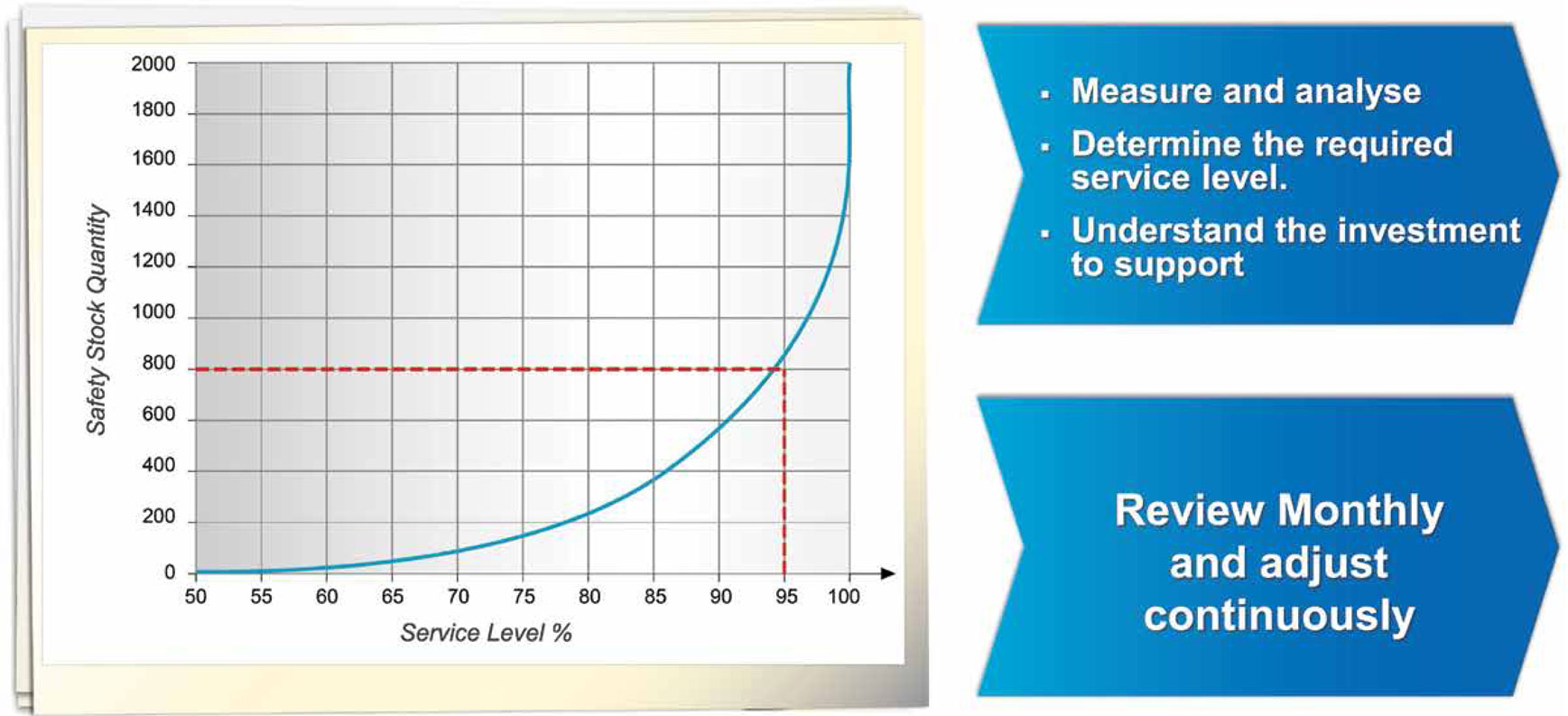

Service level vs. safety stock

As soon as a business runs above 95 per cent service levels, the amount of safety stock it needs to deliver that service rises significantly. Figure 4 shows the multiplication factor that applies in safety stock calculation, depending on the service level. When an organisation sets its service level target, it needs to carefully consider the impact this has on inventory; increasing service levels means carrying more safety stock to avoid letting the customer down.

There are two questions businesses need to ask themselves:

- Do we really need to give 100 per cent service levels?

- Do we recognise what it costs to provide 100 per cent service levels and the stress it puts on people?

In an ideal world every organisation would have 100 per cent service levels; the reality is many have to settle for 95 per cent. Benchmarking the organisation and looking at what competitors are offering, is an essential prerequisite for determining what is an acceptable service level. Look too, at what the market expects.

For example, 95 per cent may be good enough for most industries, but for the pharmaceutical and medical industries 95 per cent just won’t cut it. In the past, pharmaceutical supply chains chose high service levels over manufacturing agility, maintaining high inventory levels and carrying costs to avoid stock-outs. But with the rise of generic pharmaceuticals over patented products, coupled with the high cost of drug development, huge price pressure has been placed on the supply chain. As a result it’s no longer acceptable for pharmaceutical supply chains to carry excess inventory. But when lives can literally depend on the supply of products, pharmaceuticals must still aim for 98 per cent service levels, building the supply chains around highly accurate demand planning.

Figure 4: Service level vs safety stock

This type of market analysis must happen on a company-by-company basis to decipher what service levels the organisation can afford.

One organisation Oliver Wight worked with was faced with the task of reducing inventory by 25 per cent. For this global chemical manufacturer, there were severe financial implications of failing to meet its objective. It was clear cutting production without changing the parameters wasn’t going to do anything other than cause supply problems. The business was operating at 98 per cent service levels to achieve a competitive edge, but by dropping this to 95 per cent it was possible to substantially reduce inventory. The consequence was a slight increased risk of some customers not getting product on time, but this was far outweighed by the potential savings. The result? A reduction in safety stock worth half a million dollars.

Cycle time reduction

Another division of the same company was faced with a similar challenge of reducing inventory. But here the solution was different: the division ran long campaigns for operating efficiency but by making half as much, twice as often, it saw a substantial reduction in cycle stock. The risk was more frequent changeovers, but ultimately it would become more agile in its response to market. And with shorter cycle times, there was less chance of obsolescence. Cycle stock was reduced by 500 tonnes, with a further 150 tonne reduction in safety stock; an impressive 40 per cent of the total inventory for that product group.

Safety capacity management

Most organisations see inventory as their only option to buffer poor supply performance and provide them with the flexibility to satisfy unforecast demand. But in fact, investing in safety capacity, as part of the supply strategy, can be a cheaper option. Rather than seeing the organisation’s goal as to maximise utilisation of assets and running the plant to 100 per cent capacity, reducing its use to 90 per cent and having the ability to ramp it up when demand requires, can reduce the amount of inventory required. Flexible manufacturing ultimately reduces the investment, on-going costs and risks associated with carrying excess inventory.

Safety stock management

Normally through a lack of understanding of the true variation of demand and supply, many businesses carry a generic two-week safety stock for every product in their portfolio. But it is important to consider the significance of the individual products. Those which are more strategic or have more stringent (and even contractual) customer requirements, may require a higher service levels and hence higher inventories. Consider also those products that have such little variation in demand that safety stock is barely needed because the requirement can be predicted so accurately. If safety stock is never used, why have it? The simple rule is to put in inventory where it helps the business and reduce it where it’s surplus.

A cultural change

In changing the way inventory is managed, there will be behavioural issues and functional silos to overcome. Often it is manufacturing that dictates how much is made rather than production being based on what the business needs. Similarly demand often puts in high forecasts to make sure customers get their orders on time.

Beware of this bias in business; it kills supply chains and can kill companies. Thankfully, it’s avoidable. By having demand and supply take joint ownership of inventory, organisations can improve forecast accuracy. This joint ownership, however, involves a cultural change; breaking down departmental barriers, eliminating a blame culture and creating a team-based environment, where everyone is aligned behind the strategy.

Integrated Business Planning helps tackle these paradigms because it demolishes traditional organisational barriers and creates a structure based on integrated processes.

The challenge is to implement a change management programme in parallel with Integrated Business Planning, so behaviours are changed and the full advantages of integrated processes and teams can be realised. People must be clear about what their roles and responsibilities are. And when it comes to inventory there are plenty of people involved; critical influencers include those who effect financial, risk, service, lead-time, footprint, cycle stock, planning frequency and safety stock. Identifying these key players and equipping them with the required knowledge, allows them to apply best practice within their clearly defined roles and responsibilities. People are the organisation’s most powerful weapon for effective inventory management, and in creating a lean and agile business.

Conclusion

Inventory is not something to tackle simply when a major problem strikes. As supply chains become longer and more complex, and global economic volatility remains, taking control of inventory is essential to cost-effectively meet the demands of today’s consumer.

With an Integrated Business Planning process in place, a business will be equipped with the control, visibility and support for effective decision-making it needs to manage inventory.

Considering all the supply variables; service levels, cycle times, the utilisation of production capacity and safety stock, will reveal a list of sensible options for managing inventory. So instead of simply stopping production, the organisation can make informed decisions, more accurately predict total inventory in long- term planning and continually target reductions.

Ultimately, changing the way inventory is managed will help to create a lean and agile business.