Over many years, the business management process of choice for many organisations has been Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP). S&OP was originated by Oliver Wight in the early 1980s and although the world has since adopted the language of S&OP, it has not always adopted the fundamental practices which have made it successful.

Practitioners of S&OP continue to find that the quantity, quality, and sustainability of business performance improvements depend on how the process is used. Those organisations which use S&OP as the primary process to manage the business get the most significant and wide-ranging results. For many organisations though, possibly even the majority, their S&OP process has not progressed as the business has matured and markets changed. As a result they have not experienced the true benefits it can bring.

Integrated Business Planning (IBP) is most simply described as advanced, or next generation, Sales and Operations Planning and represents the evolution of S&OP from its production planning roots into the fully integrated management and supply chain collaboration process it is today.

Global recession, political uncertainties, and the coronavirus pandemic have each put planning processes to the test. The arrival of the economic crisis, for example, was so swift, no organisation could sidestep it. However, those which operated integrated processes fared much better during the downturn than those that didn’t. They were able to continue to drive improvement throughout the difficult times and were then ready to meet demand as it returned.

So what are the differences between S&OP and IBP and how are those organisations which have made the transition benefiting?

The evolution of S&OP

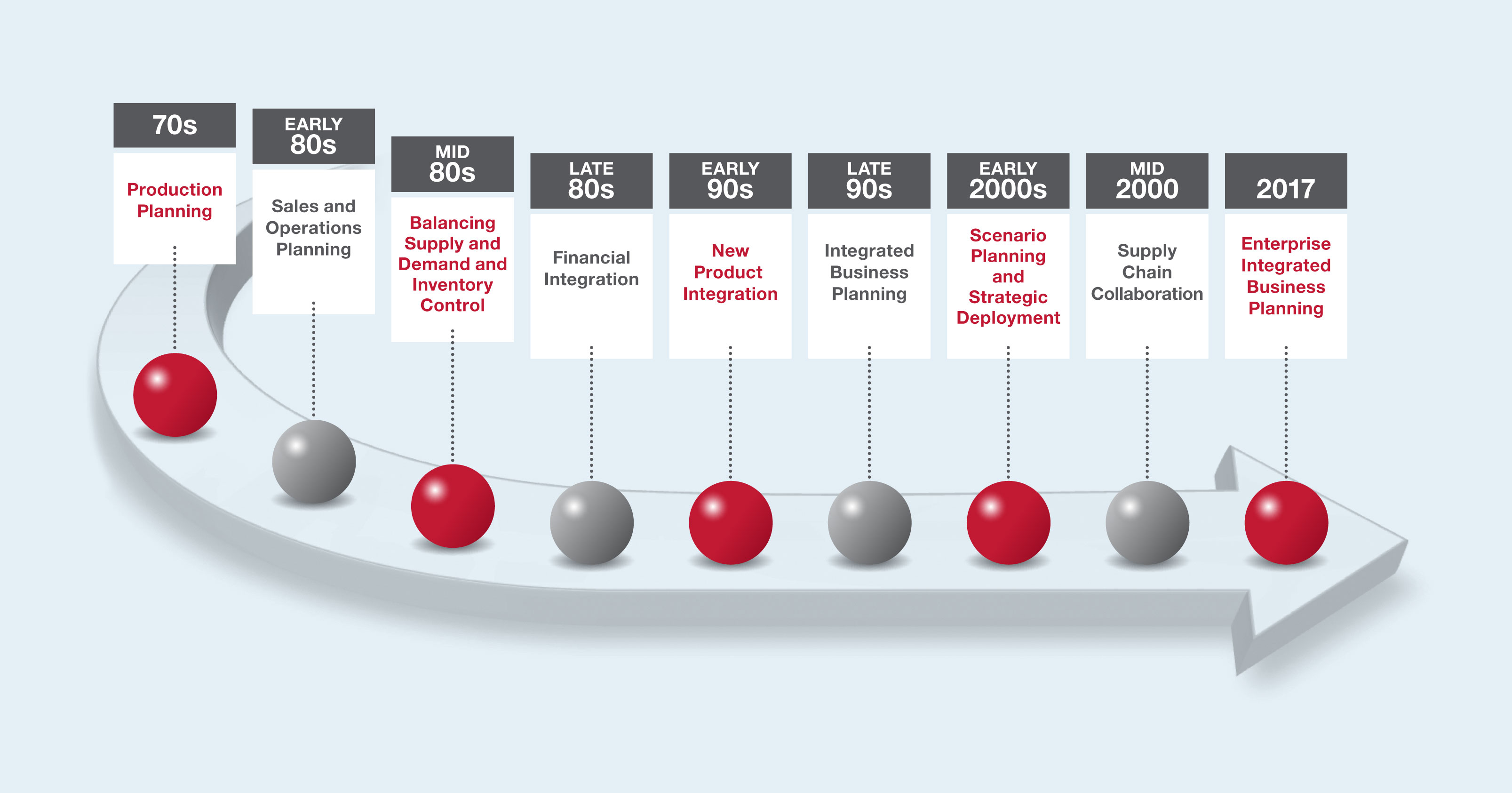

To understand the benefits of IBP over S&OP it is helpful to understand the history of its evolution, as shown in Figure 1.

Although S&OP first started to emerge as a concept in the 1970s, the acronym did not enter the lexicon of business planning until the 1980s. This reflected the first real development of the process – gaining the previously non-existent co-ordination between the commercial and supply sides of the business.

Throughout the 1980s further evolution saw the balancing of supply and demand and a focus on inventory control, but it was not until the late 1980s that the crucial development came with the introduction of financial integration to the S&OP process. This is one of the critical success factors of effective S&OP and a key aspect of the evolutionary development towards IBP.

Oliver Wight added product and portfolio management integration to S&OP in the late 1990s and many business leaders describe this as one of the highest value changes they have adopted in the business planning process. Product management is a key aspect of many businesses – for some organisations annual product churn is 80% or more. With conventional S&OP, however, product management is not integrated into the process. This leaves a substantial aspect of the business as a discrete part of planning, often viewed as a separate ‘creative’ process and the domain of R&D or the marketing department.

By the turn of the Millennium, scenario planning had become popular with businesses. This represented a significant progression from simple supply and demand planning, looking instead at the impact of proposed changes on the wider business and making comparisons against strategy. What would happen, for example, if a price change was introduced, not just in terms of profitability but on different demand scenarios and so on?

The most recent development is increased collaboration at the front and back ends of the supply chain – consumers, customers, and customers’ customers, as well as suppliers – and its integration into the process. Part of the challenge with critical suppliers and customers is developing relationships based on trust, and trust can only be generated when people deliver to expectations and to promise. This is dependent on greater reliability in the numbers and IBP does this very effectively.

Figure 1: The evolution of S&OP

Over time, the focus of attention on S&OP has been shifting toward a better understanding of the external environment as well as ensuring alignment and synchronisation among the internal functions of the company, which was S&OP’s original objective. The shift toward strategic management is a key driver in the transition to Integrated Business Planning (IBP).

So at what point did S&OP become IBP? It is important to understand that the new name was not introduced to herald the invention of a new process, but to reflect the substantial changes in an existing one. Oliver Wight and its clients started to use the phraseology in the late 1990s. Up to then, organisations were operating what they still called S&OP, but it had become a restrictive nomenclature; to many, S&OP still meant getting sales and operations together to do some planning, even though the potential of the process had already developed way beyond that. In short, S&OP no longer accurately described what the process was capable of.

Consequently, S&OP was failing to even get the attention of the executive, never mind their ownership. Whilst S&OP does not resonate with business leaders, IBP does. This is because it addresses concerns within their worry circles such as integrating and organising people within their businesses. Naturally, most businesses have a disorganised element to them; the objective is to get everybody driving in the right direction and operating to the same plan as quickly as possible (Figure 2). The purpose of an effective S&OP process has always been to achieve alignment, but whereas S&OP was just about aligning sales/commercial with supply, IBP aligns sales, marketing, R&D, operations, logistics, finance, HR; even IT. Whilst it takes time for an organisation to mature into a full IBP process, it’s important to emphasise that you don’t begin with 1970s S&OP and progress to IBP; you start with the ‘latest version’.

As consumer behaviours change within an ever-evolving digital landscape, business planning processes are also developing to aid organisations under pressure to deliver on price, choice, and convenience. Enterprise Business Planning, or EBP, develops the principles of Integrated Business Planning to provide a 21st century solution for creating a competitive advantage. EBP is not a single solution but a set of super solutions for businesses operating IBP at the highest level of technology. It incorporates digital planning capability, linking the global strategy and execution across multiple time horizons.

Figure 2: Sales, Marketing, R&D, Operations, Logistics, Finance, HR

Figure 3: Improved business results through integration, alignment and synchronisation

What are the key factors to consider in establishing a successful IBP process?

1: Ownership

Ultimately, everybody in the organisation needs to be committed to IBP (Figure 3), but that commitment begins at the top. It is critical the business leader not only supports the IBP process, but takes ownership of it and leads it. If IBP is to be the process that runs the entire business, by definition, the business leader must be committed to it; if you fail to gain executive backing for your IBP process, the process is destined to fail. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that many organisations do not grasp this fundamental principle: a survey conducted by Ventana Research shows that 70% to 80% of organisations which operate an S&OP process do not do so at the executive level; and Oliver Wight’s own poll shows that in half of some of the world’s best known organisations, the business leader does not lead the business management process. It’s not about getting the business leader to sign up to a process, it’s about the leader saying, ‘this is my process, who’s going to sign up to it?’ This isn’t playing with words. It’s transferring from the ‘dollar and cents’ page to the hearts and minds of the executives – they should be saying ‘this is what we use to run the business; to grow the business; to add value to the business’.

Figure 4:

2: Business horizon

Another fundamental of IBP is the horizon (Figure 5). Many organisations still don’t look beyond the next three to four months, or at best the end of the financial year. Successful IBP requires the business to look out over 24 months; indeed most organisations look out over 36 months or more, but 24 months is the minimum requirement. It’s critical too that it’s a rolling horizon and the forward view is continually updated with no stop/start or annual budgeting process, which the rolling forecast renders redundant. Organisations with a greater level of maturity in their IBP process use it to compare performance against strategy – the 36 month rolling plan – and are able to ask themselves whether they are headed in the right strategic direction; are the things they’re doing going to help them deliver against their strategy?

Figure 5:

The business horizon

- Identify significant problems and opportunities

- Time to determine the most effective response

- More effective annual planning

3: Focus

Important too is focus – it’s no good having a long-term horizon whilst still focusing on the short-term. Similarly, although we can, and should, learn from the past, that is only a small percentage of the IBP process. As a rule of thumb, at least 70% of time in planning review meetings should be spent looking beyond the next quarter, but our research shows that still only half of organisations do this.

The purpose of the IBP process is not to manage the short term but to focus beyond that (Figure 6); to look at the things which are heading towards the business from further out. IBP demands the business articulates where it wants to be – not just this financial year but the next few years too – and to see the financial gaps between the bottom-up ‘latest plan’ and the top-down business plan that has been financially committed to. It is still all too common for companies not to know what they are trying to achieve until just a few weeks before the financial year begins; this makes it very difficult to succeed. People are striving to deliver something but don’t know what is expected. There is an obvious relationship between the focus of the planning process and ownership of the process – if the focus is on the short term, the executive will not be interested in the process, and if the executive is not involved, the focus can only be on the short-term because those who are involved can only make short-term decisions.

Of course the long-term focus of IBP does beg the question, what about the short-term? And it’s a particularly pertinent question given continued economic and market volatility.

There is, and always will be, a need for different planning horizons (short, medium, and long-term) to be used at different levels within an organisation. Of course short-term planning and re-planning is an essential component of operational execution; without excellence in these areas organisations will fail to deliver the optimum results, both in regard to customer service and cost. But that is not the purpose of IBP. We call the short-term weekly governance process Integrated Tactical Planning (ITP). This process defines a way of executing the IBP plan whilst managing and communicating the changes that inevitably happen. The outcome is more time for senior managers to spend on strategy and the longer-term horizon.

ITP runs in parallel with IBP, feeding the individual process reviews. Companies who mistakenly use the monthly IBP process to synchronise the short-term are losing out on two fronts: it is impossible to resynchronise the short-term quickly enough, and they are missing the opportunity to use the process to regularly synchronise the medium to long term.

The role of IBP is to align all the individual functions of the business (marketing, operations, R&D etc.) to the direction in which the company is heading; the plans it has to get there; and the things it is doing based on ‘current reality’.

Figure 6:

4: Managing behaviours

As we’ve already discussed, the first challenge in implementing an IBP process – or transitioning from S&OP to IBP – is for the leadership team to take ownership of the process and commit to a new style of running the business. Then comes the sizeable challenge of overcoming the traditional thinking of operating in functional silos, and to integrate all key areas of the business. Critically, IBP aligns behaviours. One of the most common behaviours in organisations is under-promising and over-delivering because people know that will get them a better bonus or a pat on the back from the CEO. Where people are pressurised into this particular behaviour, they are encouraged to commit to things they don’t believe in. Those behaviours have to change, and the only people that can drive that change are the members of the executive team. Without change, people will start second guessing, and that leads to the creation of multiple sets of numbers, which means by the time you get to the short-term, it’s impossible to determine what is going to happen. The truth is that short-term volatility is often a result of people not paying attention to what is really going to happen or being in denial because they don’t have a definitive set of numbers to work to. It isn’t uncommon for the executive team to dismiss the bottom up numbers from their people, because they refuse to believe the truth of the fact that the plan isn’t going to be delivered; by over-writing the bottom-up plan they create the short-term volatility themselves. What is important for the leadership team to realise is that IBP is not a process for gamesmanship. Sandbagging or overly-optimistic projections are inappropriate and harmful to business performance. IBP is about communicating and discussing reality ‘as we know it’. With IBP, management is expected to either execute the consensus plan or communicate that the plan cannot be met. The principle of ‘bad news early is better than bad news late’ applies.

Keys to success

As the chart in Figure 7 shows, effective IBP requires the interaction of people and behaviours with processes and tools. We need these tools for IBP and there are a number of good IT tools on the market, which are very effective at supporting people in an IBP environment, not just for basic planning but their capability to financialise plans. But the hardest thing to achieve is behaviour change and if you don’t tackle it you will fail. Behaviour change comes from involving the right people at the right time in the right process, which is designed to achieve the right things.

Figure 7:

The importance of product & portfolio management

As discussed previously, product and portfolio management are key components in the development of S&OP into IBP. In the product management review, the focus is on product planning: analysing the product lifecycle; understanding where products are in that lifecycle; and optimising the portfolio to determine which products should be introduced or phased out. The review should analyse the product funnel in terms of the health of the pipeline – split by innovation or renovation, depending on the type of industry you’re in – plus how well projects are being managed. Its purpose is not to analyse individual projects but to understand how the business is performing against the overall pipeline; how to manage the pipeline and project status; and how to prioritise.

The key output of the product management review is an updated product plan: changes within the pipeline and portfolio need to be communicated to the rest of the business – what are the new opportunities and vulnerabilities for the demand plan; what are the key changes in supply requirements; and is alignment to the business and product strategy assured? The product management review provides an understanding of what this means in terms of the financial projections; what revenue is coming from ‘new’; how healthy is the pipeline and portfolio; and what should be rationalised in the product tail? The outcome of the review is therefore a clear understanding of the current product and portfolio management plan within the company. Most importantly, there is now clear visibility of the activities being undertaken within this core process of the organisation and the impact of these on the business plan and strategy.

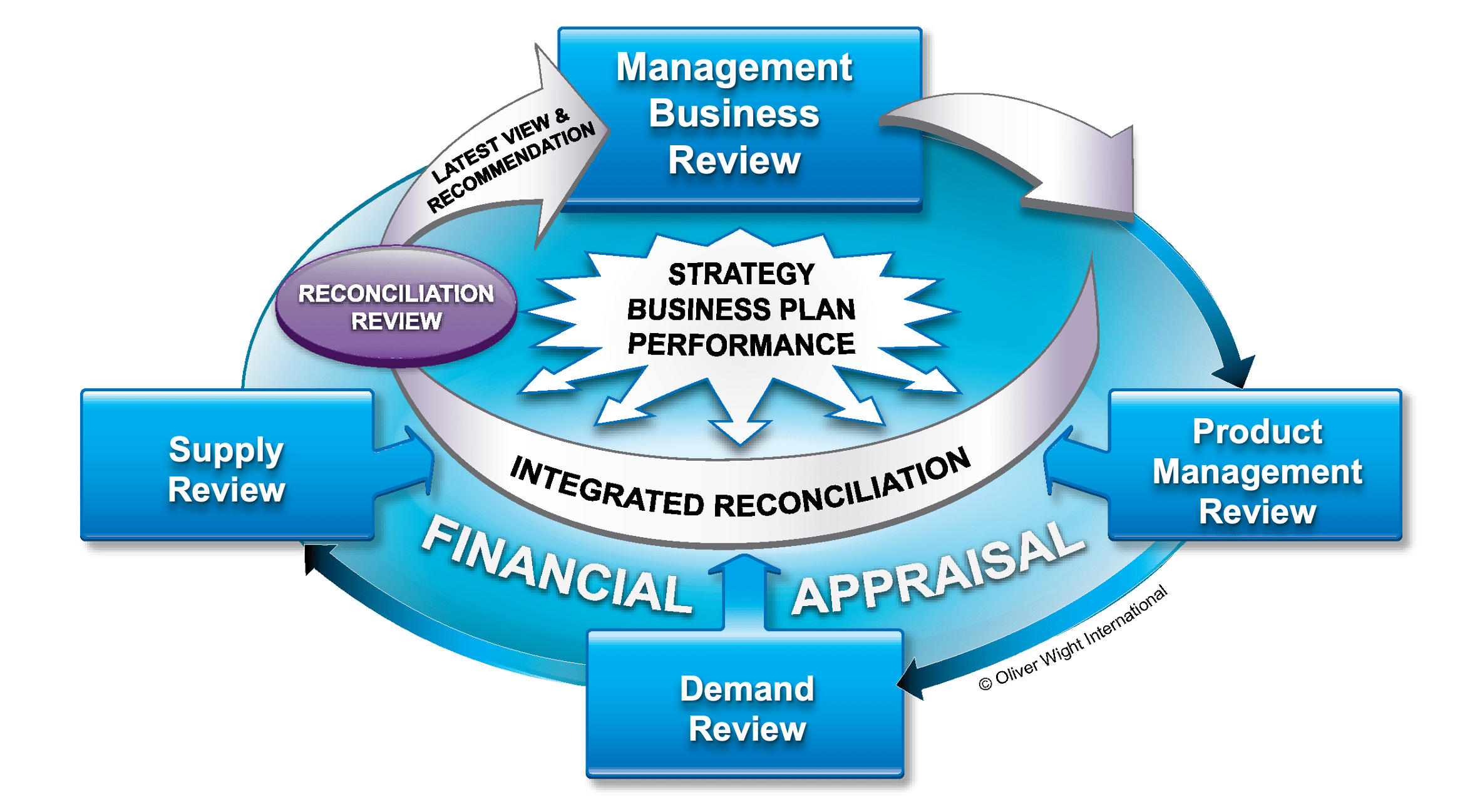

The Oliver Wight Integrated Business Planning model

Figure 8 is the process model used to depict the IBP review cycle. There are five steps in the monthly process. These are not a series of discovery meetings but a continuous process of orchestrating those who are business-accountable to review, present, and communicate progress and change. The reviews must be action-oriented, and they demand rigorous preparation to identify issues and scenarios for consideration in advance of the meeting. Then decisions can be made, and revised plans agreed, before they are made visible across the entire integrated process. The meetings are diarised from the outset and those involved have to prioritise the dates – nothing should be more important; after all, this is the management process running the entire business. The cycle begins every month with a product/ activity/ portfolio management review (depending on the nature of your business). Moving then, to the demand review (revenue and volumes). Next to supply, which needs to respond to the demand plan – in effect, a formal request from sales and marketing to the supply chain to make the relevant materials and capacity available, at the time they anticipate the customer will require them. At this point demand is understood and product management has been reviewed, so the key goal for supply is to deliver at the right cost. The fourth step is the integrated reconciliation process, which focuses on the gap between current performance, and the strategy and business plan; its purpose is to make sure good decisions are made at the fifth and final step, the management business review, which is the domain of the leadership team. In matrix organisations, there could be multiple IBP processes which run concurrently (never sequentially) up through the organisation.

Figure 8: Aligning company plans

Integrated reconciliation

This is where S&OP truly transcends into an integrated planning process. It is fundamental to IBP that appropriate decisions are always made at the lowest possible level. Gaps and their implications should be identified and understood at the product, demand and supply reviews, so the leaders of those reviews can make decisions and put forward recommendations to bridge those gaps. Thus, the business is continually optimised and re-optimised. This comes together at the integrated reconciliation review, so decisions and recommendations can be made to shape the agenda for the management business review. Another key requirement of integrated reconciliation is to understand the status of strategic activities and other programmes that do not naturally fall out of the product, demand, and supply reviews but which have a significant impact on the business (an ERP system upgrade for example); to know where they are, if they are on budget, and whether there is enough resource to manage them.

The role of finance

It is typical of conventional S&OP processes that finance is not at the table, and that financial plans and S&OP are not fully integrated. Whilst with S&OP, operational plans will come from the demand, supply, and product steps, there is often a parallel but separate financial planning process which results in multiple sets of numbers, lack of trust, sandbagging, and bias. Research from Ventana shows that only 52% of organisations have any sort of meaningful integration of plans, whilst our own study reveals that just 16% have fully integrated plans, whilst 42% have integration with financials.

With IBP, finance must have a role throughout the entire process. Within the reviews, as well as supporting processes, finance has to ensure everybody understands the financial implications of the bottom-up plans and the overall health of the business: in the demand review what is going to be sold to customers in terms of revenue and margin; for supply, what is the cost of fulfilling demand? And in the management review step, finance must be able to make a full assessment of business health over the rolling 36 month horizon – and identify gaps compared to the financial plan, the business plan, and the strategy. This assessment should include P&L projections, revenue margin, the cost implications of plans, cash flow, and income. An important side issue is that, when there is credibility in demand, supply, price, and cost data, finance is free to do value-added financial analysis instead of just forecasting.

Figure 9: How well are your plans integrated?

Information and documentation

The importance of documentation, information, and written plans is ever increasing, and this is an essential deliverable from the IBP process. Deciding which information is critical to IBP should again start at the top. The key is for the executive to understand which information they need in order to make real decisions that help influence the future performance of the business. Real understanding of markets, customers, internal capabilities, as well as strengths and weaknesses is vital to allow the formulation of a quantitative and qualitative plan with a clear understanding of the impact they will have, so the management team is in a position to truly optimise the business.